Rebien: Novo-workers contribute or they are cast out

The baptism of fire came in 2001.

Lars Rebien Sørensen had headed the Novo Nordisk group for less than six months when he and the company had hit a rough patch, because the Danish company along with 40 other drug groups had sued the South African government in a case revolving around patent rights for drugs to treat HIV. It was a somewhat younger Lars Rebien Sørensen who took the bull by the horns, as it were, took of his tie and put on his leather jacket and marched out to meet the protester who had gathered in front of Novo’s plant in Nørrebro. The new leader passed with flying colors.

He did so by relying on what would turn out to be a mantra for the company’s management in years to come; openness. Instead of trying to gloss things over and turn focus away from the matter at hand, he met the accusations head on. Yes, we make money off of ill people. No, we are not a humanitarian organization. And no, we will not change our attitude and give up our drug patents.

“I was angry. I thought the critique was unfair. Carsten Jensen, the blessed author, described us as Nazi-pigs in a feature article. It was blown completely out of proportion and it made me damn angry. It was a case that directly related to our reputation and therefore it was important to act to the outside world. But also to the world inside the corporate walls, so our employees didn’t get the impression that we really were Nazi-pigs,” Lars Rebien says without the slightest hint of a smirk.

Defining his own role

In the beginning of his reign, the CEO had a more masculine and aggressive approach to management. 13 years have passed since then and sitting in the top floor of the new head quarters of the company he helped make one of the most valuable in Scandinavia, he admits that he might have grown a little softer with age – in some regards.

“Originally, I came from the business side of Novo Nordisk, much like Kåre Schultz do now. That’s the sharp end of the business, where you need to make tough decisions about budgets and about whether or not people will have job opportunities. It requires you to be a bit thick-skinned,” he says, adding:

“I have had to redefine my own role to encapsulate everyone in the company, also the people in the research department who have burning desires to create a new drug and are not necessarily too hot on making money. Whereas I came from the end of things where we had to make money, I’m now in a place where I have to make everything come together in the sense that, of course we have to make money, but we have to do it in the right way, so we can look at ourselves in the mirror.”

“It might be an accurate description that I have grown softer, but I also believe I have grown sharper in some respects. I have become more aware of what I will tolerate and what I think the company should tolerate. There are sharper edges in our relation to the press and parts of our surroundings which affect us.”

During your management period, Novo Nordisk has gone from 6,000 to 38,000 employees. What is your own greatest strength as a leader in that process?

“I don’t think of it in those terms. To me it was just as difficult when there were 6,000 as it is now. The management team expands as well. What’s more difficult is reaching out to people. We have better means of communication today, which give you a wider reach, but keeping the personal contact becomes more difficult. You only have so much time in the world. Other than that, the difference is not so big.”

You often hear about a special Novo Nordisk spirit, a strong culture. Can there even be one unifying culture among 38,000 employees?

“I hope that there is a special feeling and culture in the company. We certainly work at creating just that. But at the end of the day, it’s the employees who can tell us if such a culture exists.”

How do you create one culture in such a vast corporation?

“If you want to succeed in that, you have to create a coherent corporate story. Call it what you want, but simply put, it’s a matter of describing clearly what the company stands for and where the company is trying to get to. It has to be described in a way so that employees, potential employees and stakeholders outside of the company can all identify with it and identify the company with it.”

A Danish company

It is in that process – in creating that narrative – that you have to be careful to create something that is on the one hand motivating and ambitious, but on the other hand not unreliable, Lars Rebien explains. To create a narrative about a company takes time; you first have to gather inspiration. The CEO spent about 18 months on the latest in the line.

“I helped create the first, Novo Nordisk Way of Management, in 2000 and we updated it about three years ago. Now it’s called the The Novo Nordisk Way. In that process, you have to make some choices as to what your business aim is, which values should characterize the company, and which identity you emphasize. We put a lot of emphasis on the fact that we are a Danish company. That’s very deliberate, from the mindset that we want to have a bit of an edge. We don’t want to be a multinational company with no identity and no historical relevance or significance,” he says and goes on:

“It’s necessary to train your employees. The Novo Nordisk Way is a part of the introduction for all new employees and it is a part of the target contracts of the managers that they live up to the Novo Nordisk Way. And we follow up on that and evaluate.”

What do you do if the managers fail to live up to that?

“Then we help them. We have a set of experienced senior people that we call facilitators who go around and every department will get a visit from them at least once every three years.”

Those visits usually focus on evaluating the work in a given department, such as a manufacturing or research unit, where it is examined if there is a proper work environment, whether the manager lives up to the value statement, if the department has business plans, if they have an overview of rules and regulations within the field they are working in, etc.

When it starts to become a problem

“If you are not getting it quite right, you might need help. If, for example, you are a new manager in our Korean unit, the values entailed in the Novo Nordisk Way might not come natural to you in a Korean context. Then you can be helped by one of our facilitators,” Lars Rebien explains and adds:

“If you still don’t get it, then it starts to become a problem. The facilitators make a deal with a given manager that he or she can and will improve on a number of things and that’s meant to help, but if the manager doesn’t understand it or is unable to improve, he or she might need a different job within the organization that doesn’t involve management. If they are still unable to adapt, then they probably don’t belong in the company. Then it will have consequences. We are unrelenting in that respect.”

How would you characterize a good Novo Nordisk manager?

“People who are committed. In Denmark, we are able to attract the people with the best competencies that you can get in terms of education and experience, so most of the time it’s also people that are highly skilled professionals and are very ambitious. Those three characteristics; commitment, skills and ambition, might sometimes result in too much individual focus on your own career, so it’s also important that we explain to people that they can’t carry the burden all alone. They have to work together with others to achieve results,” the CEO says, before elaborating:

“There is an old native-American saying that describes it quite well. If you want to travel quickly, travel alone. If you want to travel far, travel together. We don’t want to be too quick, we want to be sustainable in the long run.”

If the company has a strong profile and a strong history, it will attract the people that such a profile and history resonates with.

“The ones it doesn’t resonate with will leave the company, either because they don’t feel their potential can be developed, or because they are asked to. We create a culture that attracts people who support that very same culture. We have largely succeeded in that, so I’m no longer the guardian of the Novo Nordisk spirit and virtues; the entire organization is.”

How do you feel about the employees that you yourselves have called ‘actively uncommitted’ in your surveys? Is there room for them in that culture?

“We have to admit that people often stay with Novo Nordisk for the duration of their professional lives. I also try to tell managers that there are various phases of your life. Your level of commitment can be affected by your family situation, with disease and such. The company should be sensitive to that and accept that there might be periods of time when people find their families more important than their careers. But then they obviously can’t expect the rest of the company to lay dormant, while they spend time with their families,” is the blunt message from the Novo chief, before he moderates it:

“But we also have to be accommodating of that. We can’t have teams made up entirely of star performers. We have a range of jobs that need doing and they have to be done conscientiously and properly. But if people are down-right uncommitted, I think the corporate culture is so strong that it will gradually cast them out. People who don’t contribute are eventually expelled from the company; like an unsuccessful transplant in which the body’s immune system rejects the organ.”

The incident in 2001 in front of the protesters helped cast you in a certain light as a leader from the offset. Can you mention other events that have helped form you as a leader?

“There have been a few others – on an internal basis – where we have been forced to make business decisions based on mistakes. There have been some business-related things that haven’t worked out for us, where we have been forced to make major strategic decisions afterwards. The lesson I have learned during all the years I have been a part of this is that those are actually the most interesting times – even if it doesn’t feel all that pleasant when you are in the midst of it,” Lars Rebien explains, elaborating:

“You make some decisions that you maybe should have made earlier on. It is spelled out to you, you might become more willing to make major decisions, and the organization might also be more willing to accept major decisions when they are made on a burning foundation. It’s more difficult to build that foundation for making major changes on your own.”

Do you have a role model as a leader?

“No, not really. If I were to say ‘I think I will emulate Mads Ø’, then I would tank completely. I’m not [former Novo CEO] Mads Øvlisen. It’s well-known that he is very culturally interested and has utilized culture and art to create an understanding within and around the company. I know nothing about art; I come from a totally different background,” he says and adds:

“So I have had to create my own. I have no role models; I can’t really use them for anything because they are not me.”

My job is my podium

Over the years, many business leaders have desired to take center-stage to a much larger extent than you. But you have maybe stepped forward a bit more recently. Is that because you feel a need to call out the politicians?

“I think there’s often no connection between what politicians say and what they do, and I see that as a huge democratic problem. The current government was elected on a welfare agenda aimed at increasing the public sector on the back of a decade of starvation during the reign of a non-socialist government. Then it turns out that they actually cut back on the public sector and welfare. That has consequences for the people who voted for the government. It leads to polarization and distrust,” he says.

“The podium I stand on is my job. No one is interested in what Lars Rebien believes outside of that. It’s only because I have this job and you have to be mindful of that. Some of my colleagues go out and comment on every little thing and I don’t think you can do that. But I have a legitimate right to speak about the things that affect our company and where I believe improvements can be made.”

So you have no wish to invite people into your private sphere?

“No, I don’t find it relevant. I really don’t like the current trend of drawing your family into your public life; they should be spared of that. It’s enough that the papers write about how much money I have and my children are confronted with that. In my view, that part serves no purpose. I want to keep it to myself.”

If he can make it there…

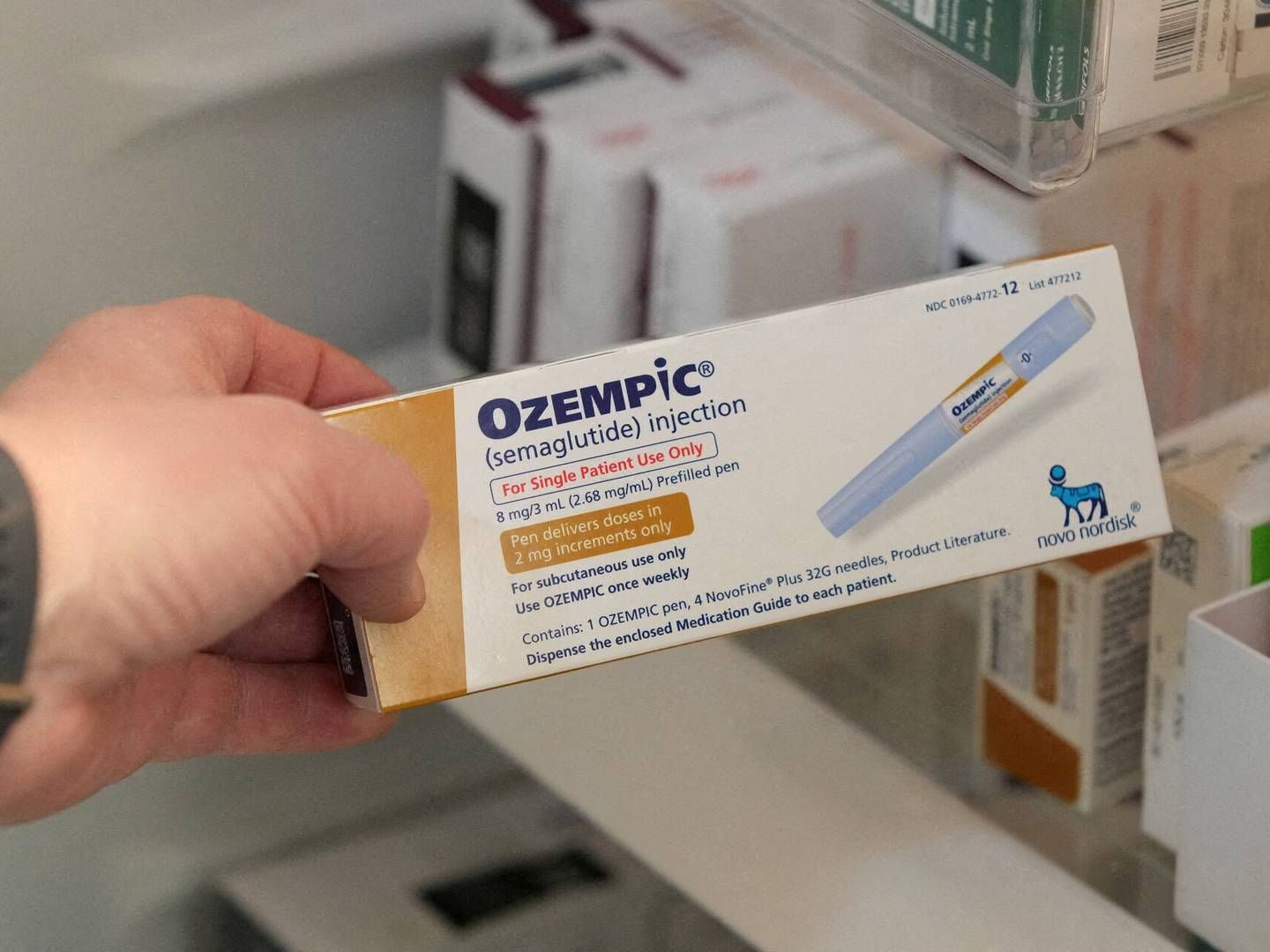

Lars Rebien’s podium has taken him to global platforms, especially to the United States – the world’s biggest market for prescription drugs. Consequently, he has joined the influential US industry association, PhRMA. It’s on the global stage that Novo’s interests are greatest; that is where revenue and growth lies for the company. Less than 0.5% of revenue comes from Denmark.

“We are world famous in Denmark, so I have to spend most of my time profiling the company outside of Denmark. I have to ensure that Novo Nordisk understands the political environment in the US and understands where the whole regulatory area is headed, so we are better equipped to act as a company. We might also be able to influence those developments, to ensure that our point of view comes across. We prefer openness and want to enter into dialogue with our critics, which is not what characterizes most American companies. They like to keep things at arm’s length,” he says and stresses:

“We are now so big that people listen to us; they didn’t use to when we were nobody. But even in the US, they know who we are now. I hope we can learn something and maybe also push developments in a direction that benefits Novo Nordisk.”

A few months back, executive vice president Kåre Schultz was named vice-CEO. The move was seen as an appointment of a deputy and eventual successor to the CEO. But Lars Rebien Sørensen, who recently extended his contract with the board of directors until 2019, has no intention of abdicating his throne anytime soon.

Wanted: Top talents with the right level of commitment

Rebien: The strongest pipeline ever

- translated by Martin Havtorn Petersen

Would you like to receive the latest news from Medwatch directly in your e-mail inbox? Sign up for our free english newsletter below.

Relaterede artikler

Rasmussen outperforms Rebien

For abonnenter

Rebien’s hidden agenda

For abonnenter